Our health is determined by our genetics as well as our lifestyle habits. Their roles are best captured by the phrase “our genetics load the gun but our lifestyle pulls the trigger”. If the gun is heavily loaded because of unfavorable genetics, even a slight pull of the trigger in the form of small deviations in lifestyle will have grave consequences. Conversely, if the gun isn’t loaded as heavily because of good genes, a larger deviation in lifestyle from optimum may not impact one’s health as much. While I have devoted most of my posts about the lifestyle changes I have made over time to improve my health outcomes, today’s post (#37) covers the genetic aspect of my journey. More specifically, I write about my personal experience using nutrigenomics: exploring the relationship between genetics, nutrition and metabolism, and health outcomes, to understand how my lifestyle can be personalized based on my genetic makeup, to optimize for my health and to minimize my probability of disease.

Before I dig into the details, I should mention that this post has more images than my other posts, with screenshots from my nutrigenomic report as well as of my various blood test parameters. I realize I am sharing a lot of information that should ideally not be in the public domain for a number of reasons. However, I realize that posts like these are only credible when there is supporting evidence; I have accordingly chosen to show enough data to ensure credibility, while not going overboard. Also, anyone listening to the audio version will get the full benefit if you can also see the accompanying images in parallel.

The Basics of DNA and Mutations

DNA is the instruction manual inside our cells that guides how our bodies grow, function, and develop traits. It’s composed of 3 billion nucleotide pairs represented by four "letters"—A, T, C, and G (adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine). These letters pair up (A with T, C with G) to create a unique code. Within this code are specific sections called genes, which contain instructions for making proteins. Proteins perform essential functions in our bodies and influence traits like eye color and metabolism. While genes make up only part of the DNA, they play a crucial role in life’s processes.

Each gene exists in a certain "standard" form, known as the wild type. However, sometimes mutations or variants occur in many of us, leading to slight changes in the gene's structure. Genetic mutations can have diverse impacts; from neutral with no effect, to being beneficial, like improving disease resistance, to causing physical trait differences like eye color, to increasing the risk of diseases (e.g., BRCA mutations linked to breast cancer). Severe mutations may result in developmental disorders like cystic fibrosis.

Understanding Nutrigenomics

Nutrigenomics is an emerging field that combines genetics, nutrition, and molecular biology. Nutrigenomics research has provided valuable insights into how genetic variations affect nutrient metabolism, disease risk, and individual responses to diet and lifestyle factors. Personalized nutrition based on nutrigenomic insights has shown promise for improving health outcomes, particularly in managing metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. By understanding genetic predispositions, clinicians can tailor dietary, supplementation, exercise and even sleep recommendations to better suit an individual's needs.

A nutrigenomic analysis can provide insight into various aspects. Here are a few examples:

Metabolic Efficiency: Some gene variants alter the way certain enzymes work. For example, variants of one particular gene can affect how efficiently the body processes folate, a B vitamin crucial for cellular function. People with certain variants of that gene may need more folate or might benefit from a specific form (methylated folate) to meet their nutritional needs.

Fat and Carbohydrate Processing: Variants of certain genes can influence how a person stores fat or processes carbohydrates. For example, some variants of one specific gene are associated with an increased risk of weight gain with high-fat diets. Knowing this can guide individuals to adjust their fat intake to help maintain a healthy weight.

Lactose Intolerance and Food Sensitivities: Variations in specific genes can cause sensitivities, like lactose intolerance. People with these variations might need to avoid or limit foods like dairy to feel their best.

Detoxification and Antioxidant Needs: Some gene variations affect how well our bodies clear out toxins or handle stress from things like pollution. Those with certain variations may benefit from eating more antioxidant-rich foods, like berries and leafy greens.

Sensitivity to Caffeine or Alcohol: Genetic differences can make some people more sensitive to caffeine or alcohol, meaning they should limit these to avoid issues like jitters or feeling unwell.

However, human metabolism is highly complex, and diet-related genes don’t act in isolation. Lifestyle, environment, and other genetic factors also play significant roles, making it challenging to draw definitive conclusions based solely on nutrigenomics. While some gene-diet interactions are well-documented, others are less clear, and not all nutrigenomic tests are equally evidence-based. Research is ongoing, and many findings still need further validation through large-scale studies. As technology for genetic testing becomes more precise and affordable, and as databases expand with more genetic information, nutrigenomics is expected to become increasingly evidence-based. This will improve its clinical validity and reliability.

Given the promise as well as the challenges of this evolving field, I am sharing my personal experience and usage of nutrigenomics to impact my day to day lifestyle decisions.

Deep Dive into my Nutrigenomic Data

Let’s start with the sections my nutrigenomic report covers: Diet, Nutrition, Sports and Fitness, Lifestyle Conditions, Metabolic Core, Digestive Health, Addictions, Sleep and Rest, and Allergies and Sensitivities. There were 654,027 of the 3 billion nucleotides analyzed for 206 different health conditions in this study. In the interest of keeping this post readable within 15 minutes, I have only covered the sections highlighted in bold above. Even within these few sections of the 54 page long report, there is a lot of information in each of the sections. Therefore, I am going to focus on the few parameters within each section (you will see screenshots of my report in the images below) that either validate my current lifestyle, or ones that justify the need to make changes to my lifestyle in the form of new habits or supplements. For the validations or to justify the lifestyle or supplementation changes I have made, I have highlighted the relevant blood test parameters from my regular check-ups in the images below.

Diet:

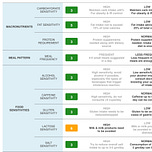

Historically, I used to be a snacker consuming a lot of small meals but, since my diagnosis 9 years back, I switched to consuming a few large meals. This consumption pattern is more in line with my genetic predisposition (see the “My Meal Pattern” section in figure 1 below).

On protein supplements, my report suggests that intake through diet is enough for me (“Macronutrients” section “Protein Requirements” subsection in the image below). However, since I am mostly vegetarian plus “chickenatarian” and the fact that I do strength training 3 times a week, I observed in my Body Composition Analysis results that my muscle mass wasn’t increasing. This was because the amount of protein intake from my diet wasn’t enough. I therefore chose to take a protein supplement, but I keep a close eye on my kidney function markers, such as creatinine, eGFR, uric acid and liver function markers, such as ALT and AST. I have been able to increase my muscle mass pretty nicely while keeping the above markers under control.

I have always been lactose intolerant (“Food Sensitivities” section “Lactose Sensitivity” subsection in the image below) to the point that I had a gag reflex while drinking milk when I was younger. However, I seem to be ok with ice-cream (in case you want to send me edible gifts for Christmas, I just wanted to clarify this) and yogurt. I have stayed away from milk for the last 40 years and have empathy for any kids whose parents are on their case to drink milk.

I have started keeping a closer eye on my fat consumption (“Macronutrients” section “Fat Sensitivity” subsection in the image below), specifically looking at the amount of unsaturated (healthy) fats vs saturated (less healthy fats to be kept to 10% of total daily calorie consumption) fats. While my daily fat consumption is closer to 35% to 40% of my total calories, I am trying to have about 70% or more of my fat calories be unsaturated fats (chia seeds, quinoa, nuts, avocado, olive oil, etc.).

Figure 1

Nutrition:

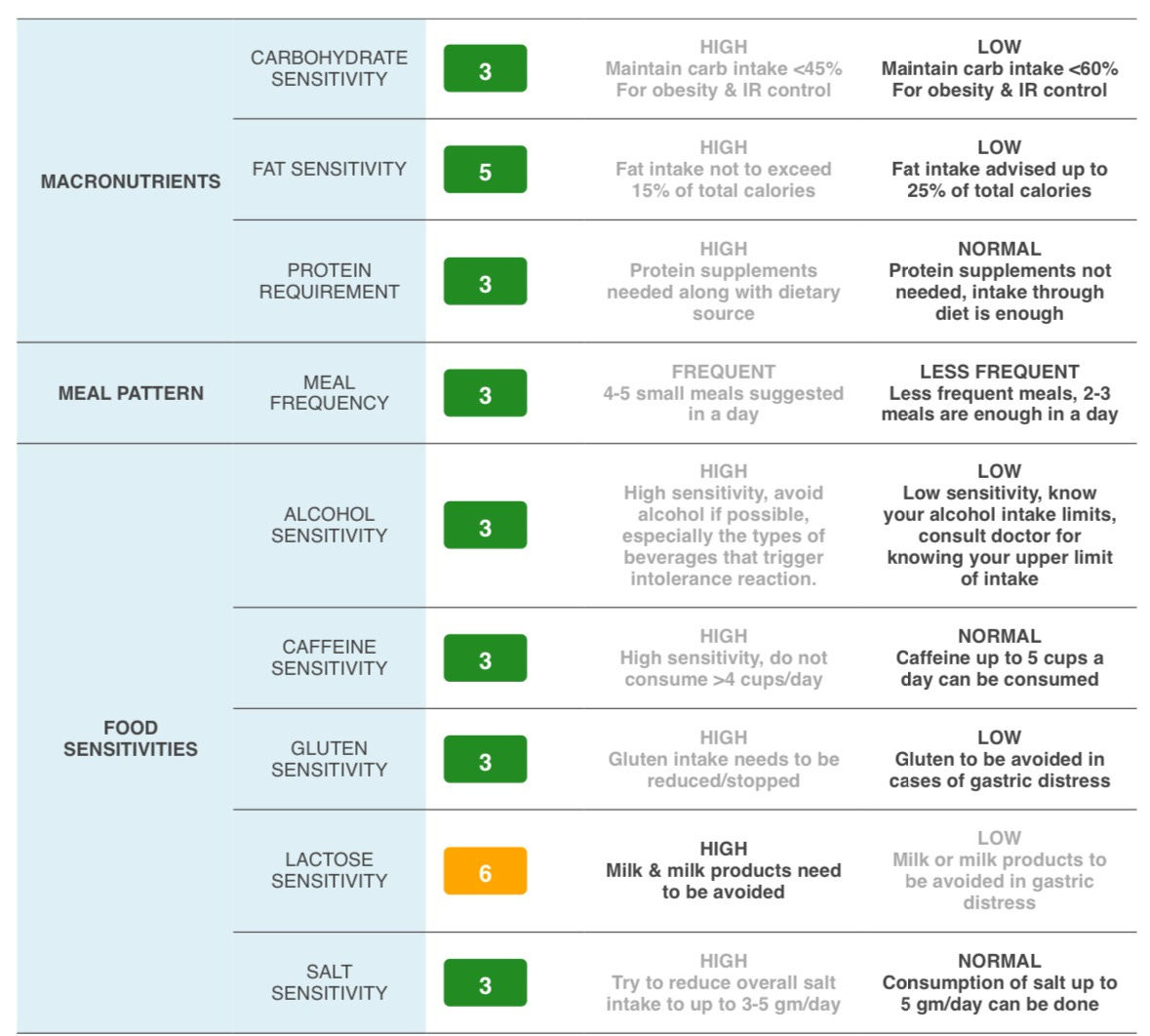

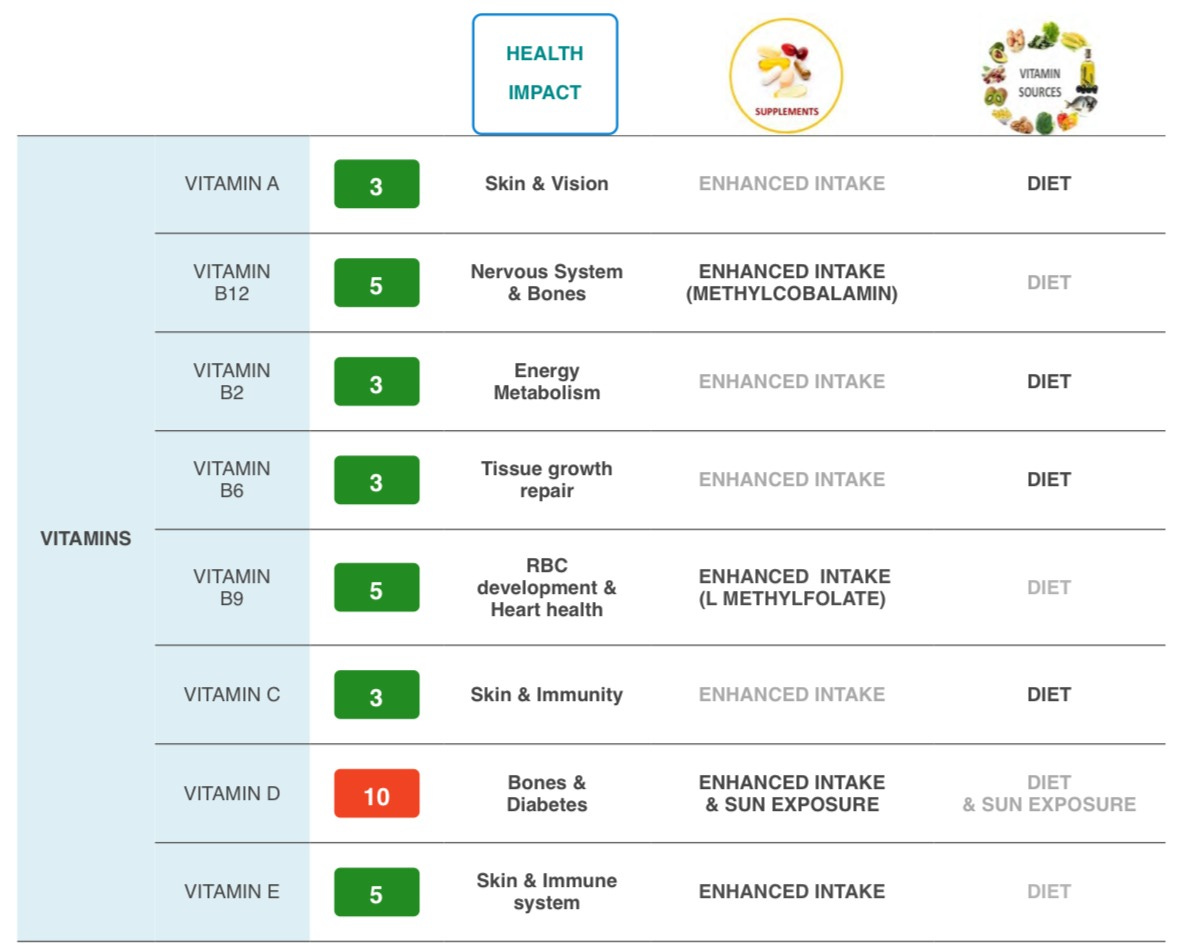

While the report below (Figure 2 below) suggests that I need to supplement Vitamin B12 (by taking methylcobalamin) and Vitamin B9 (by taking L methylfolate), I looked at my blood test results for my Vitamin B12 levels (Figure 4) and found that they were well within range (I didn’t get a B9 measurement unfortunately).

However, my Vitamin D result from the nutrigenomic report (Figure 2 below) was as damning as one can get and my blood test results (Figure 5 below) validate that need very convincingly (my vitamin D levels were low and it required me to take supplements to bring them up within range).

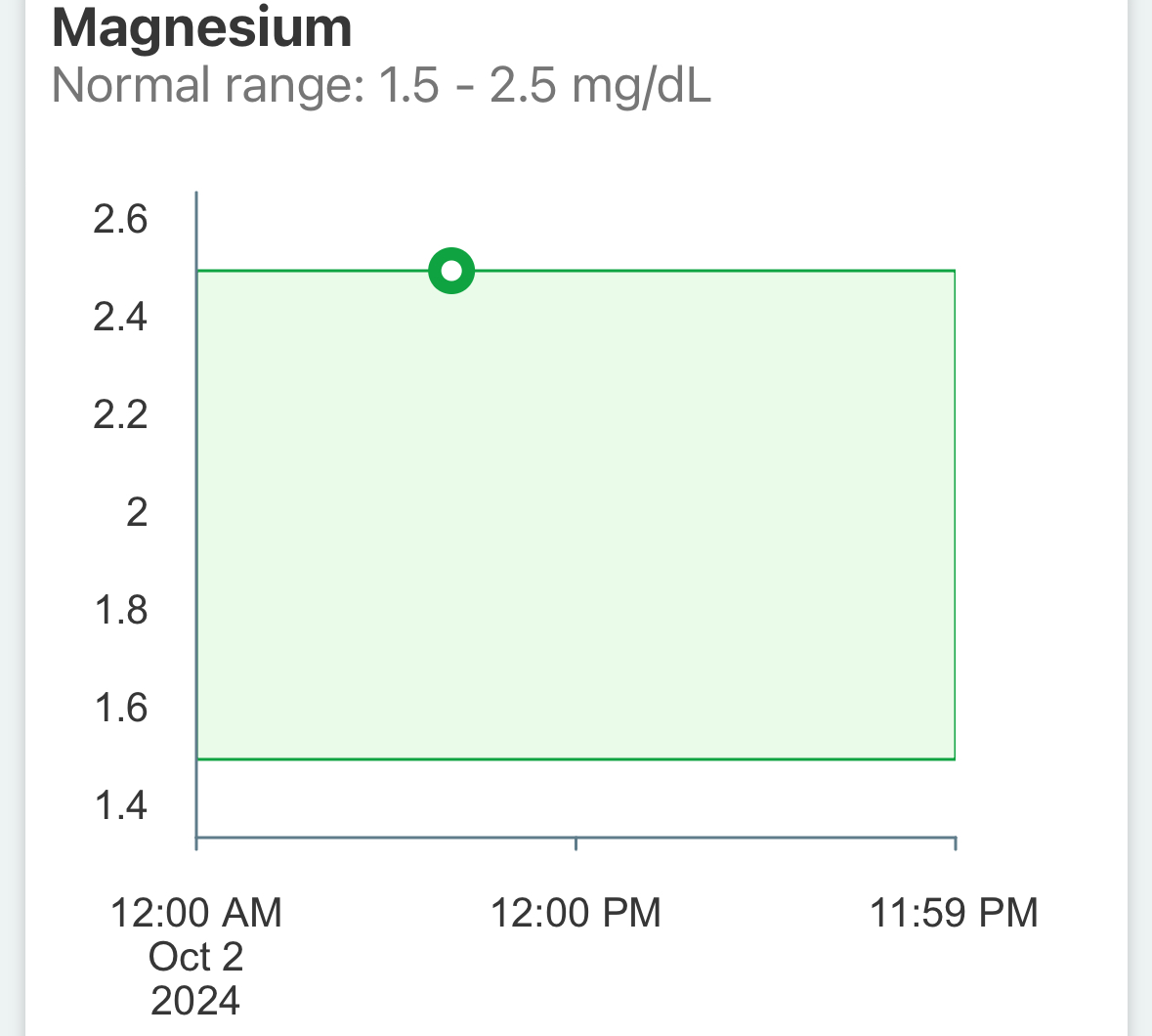

The need for magnesium supplementation is orange as per the nutrigenomics report (Figure 3 below) and is something I took for a while to help with my sleep, but my blood tests results (Figure 6 below) showed that my magnesium levels were within range so I have decided to stick to getting it from my diet alone.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Sports and Fitness:

The three takeaways in yellow boxes from the nutrigenomics report (Figure 7 below) are all validations of observations I have had:

An increased water and electrolyte loss which goes hand in hand with the increased probability of muscle cramps. I can’t begin to describe the number of times after a game of soccer, I drank water but I still got a really bad case of muscle cramps in my legs that were debilitating. I realized I needed to drink more water than I thought I needed and that too with enough electrolytes added in, to avoid the cramps. Since that change, I have almost never experienced any cramps.

On the point about increased injury risk, until about three years back, there were very few times I came back from a game without some sort of back or knee injury. As I have written previously on this topic, these injuries dropped quite dramatically after I added in strength training 3x a week. If I had done my nutrigenomic study a few years ago, I would have probably not had to learn some of these lessons the hard way.

Figure 7

Lifestyle Conditions:

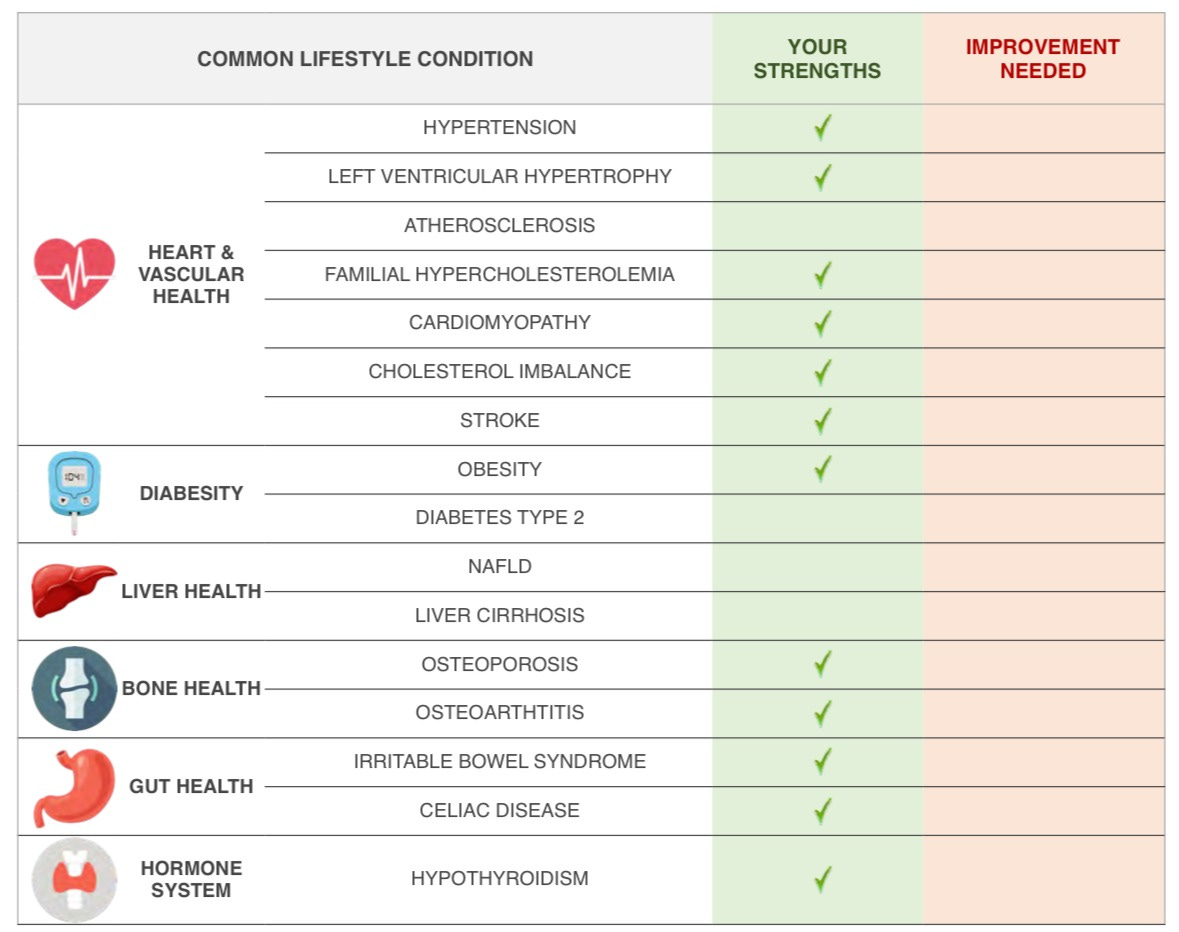

The three areas that showed up as being potential issues in the “Improvement Needed” column of the nutrigenomics report (Figure 8 below) are my risk of atherosclerosis (the risk of build up of plaque in the walls of the arteries), type 2 diabetes, and liver related issues (NAFLD or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cirrhosis which is the more extreme version of NAFLD). All of them are considered lifestyle diseases; however, my genetic predisposition meant that my chances of developing these diseases was higher compared to someone whose genetic risk was lower, if both of us consumed the same food, exercised the same way, etc..

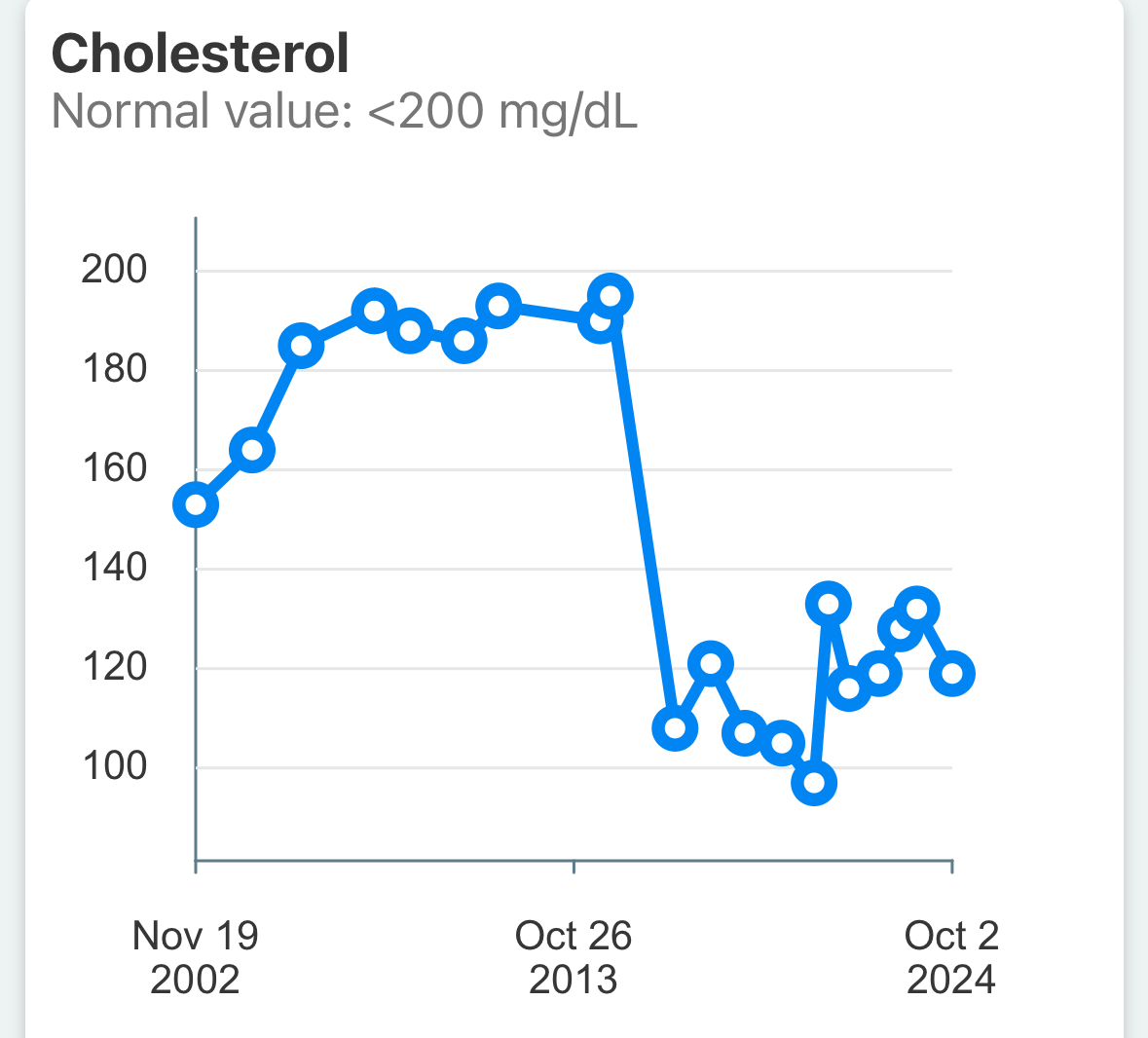

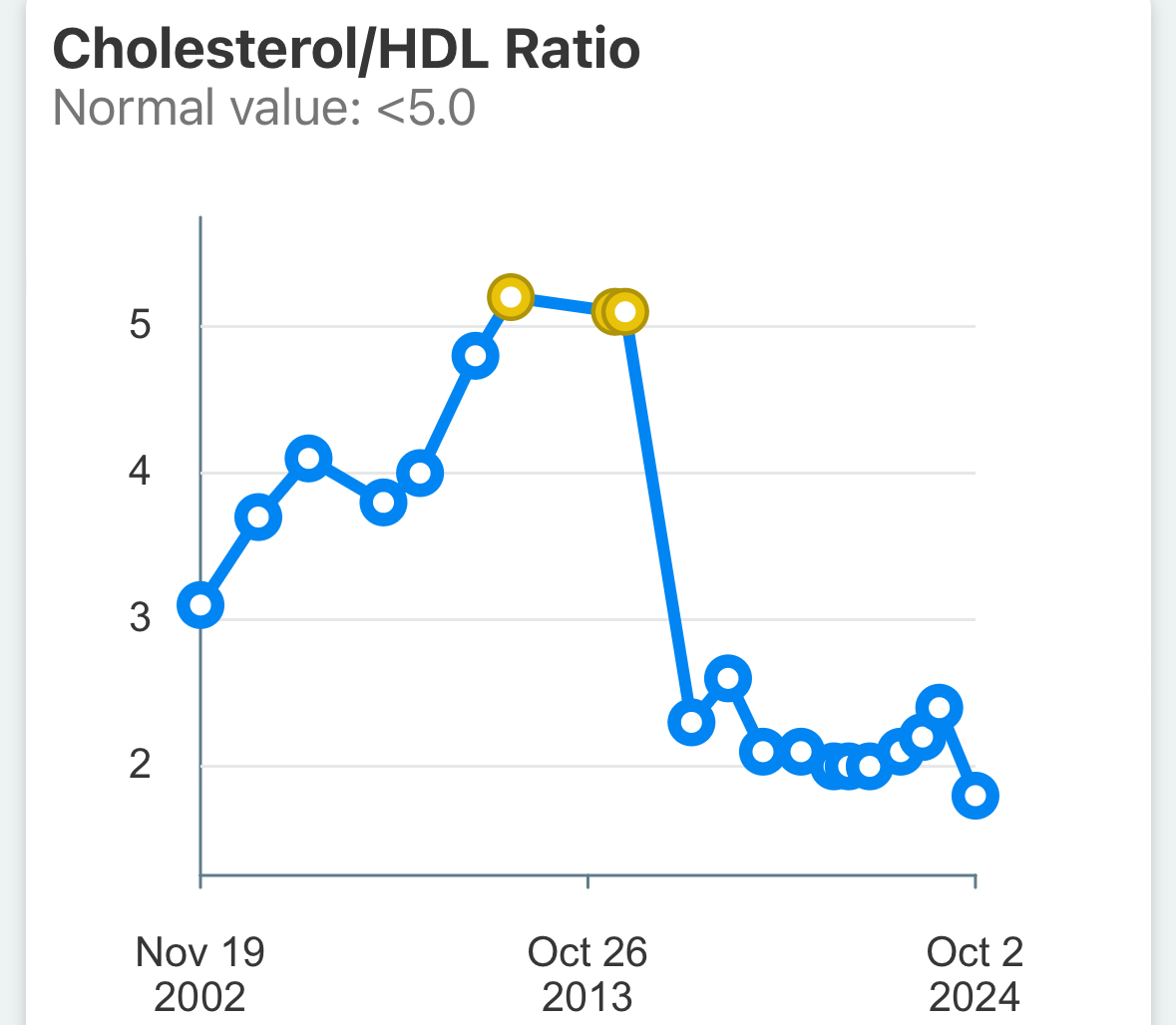

Given my genetic predisposition to atherosclerotic risk, the fact that I was diagnosed with coronary artery disease (CAD) aka heart disease viz. the build up of plaque in the coronary artery shouldn’t have come as a complete surprise. If I had known this risk 20 years ago, maybe I could have been more careful with my lifestyle habits. Had this been part of standard testing in my 20s, I should have been on the radar of my medical system. In the image below (Figure 9 below), check the gradual rise in my total cholesterol levels from 2002 onwards until 2015 when I was diagnosed with heart disease. I never crossed the magical 200 mg/dL total cholesterol level because of which I was never flagged as at any significant risk because neither of my parents had been diagnosed with any heart issues until then (my dad eventually was diagnosed). However, the combination of my genetic risk and my increasing cholesterol levels together could have potentially flagged the issue. One of the things that can be misleading about using the total cholesterol number is that it is the addition of LDL-cholesterol and VLDL-cholesterol (in both cases lower is better) and HDL-cholesterol (where higher is better). This makes total cholesterol a funky number to interpret. An alternate metric used, which I have shown (Figure 10 below), is the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol, where we want this ratio to be as low as possible. Note that while the total cholesterol marker paints a confusing picture about my numbers between 2015 to 2024, the total cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol ratio paints a much clearer picture that my numbers are the best they have been. While the statins helped drop my ratio to 2.5, continual lifestyle changes have now dropped that ratio to 1.8. This is because my LDL-cholesterol continues to remain low while my HDL-cholesterol has been increasing nicely. It is interesting to note that the origins of that 200 mg/dL threshold lie in the 1948 Framingham Heart Study, which identified cholesterol as a key predictor of heart disease. This study, conducted on predominantly white, middle-class Americans, has been shown by the South Asian Heart Center and others to not be as relevant for most other ethnicities, and needs personalization even for the Caucasian population, based on their genetics, lifestyle and comorbidities. As I have noted in my post #2, there are many other markers that, together with those used in the standard lipid profile, are more comprehensive indicators of heart health. As you can see, the impact of my medication

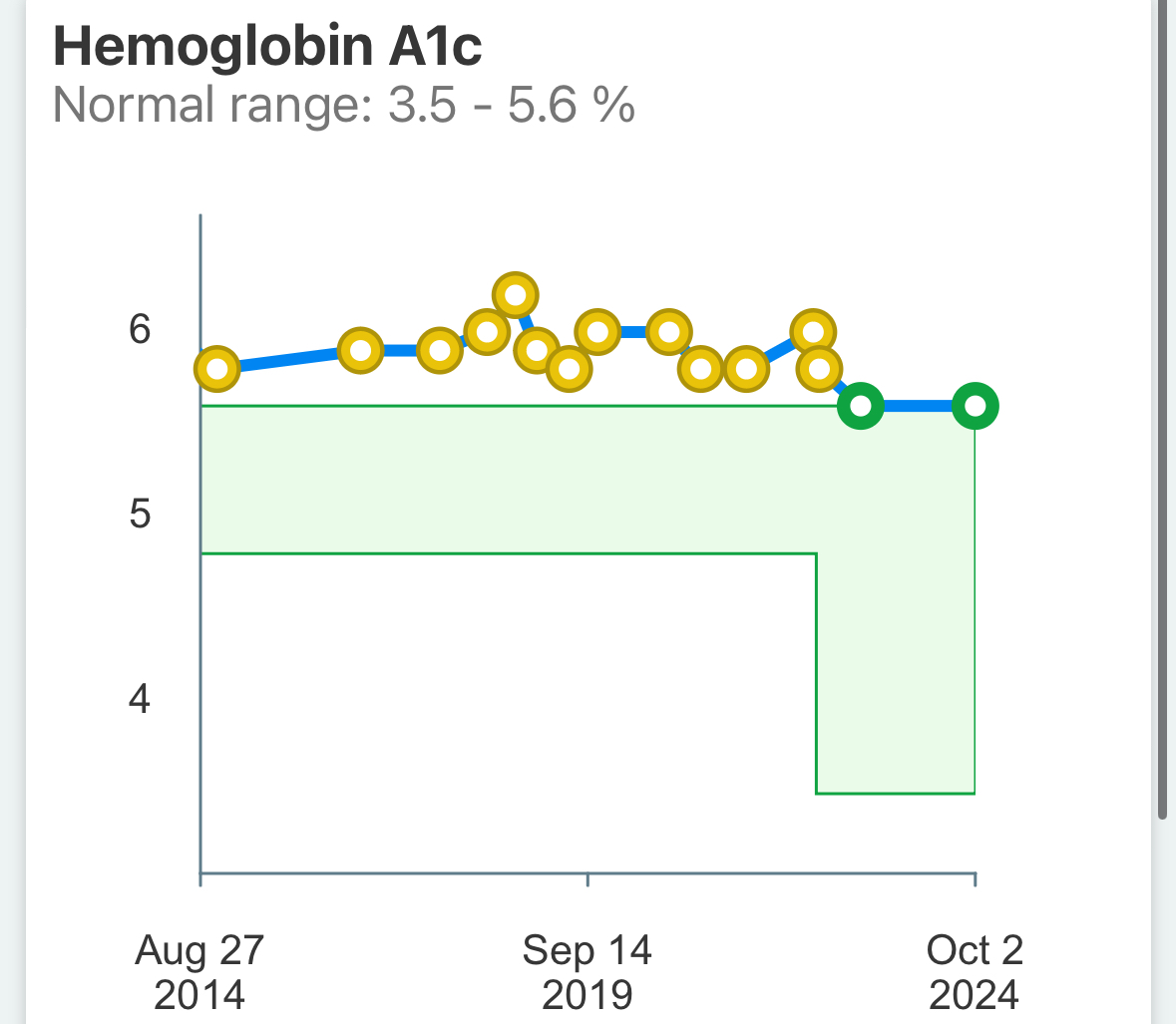

Similarly, my genetic predisposition to diabetes, which manifests as a high HbA1c value (Figure 11 below), was in the pre-diabetic range even a year before my diagnosis and then continued climbing into the 6+ category even after my diagnosis (which got me close to the diabetic range). I was put on a small dose of statins to help stabilize the high level of plaque in my arteries and that is known to have a negative impact on the HbA1c marker. This meant my lifestyle needed to work doubly hard to fight against both my genetic risk and the impact of the statin. As you can see, my HbA1c is now at the lowest level it has been over the last 10 years in spite of the statin and, for the first time since I started measuring this marker, has fallen below the pre-diabetic into the normoglycemic range.

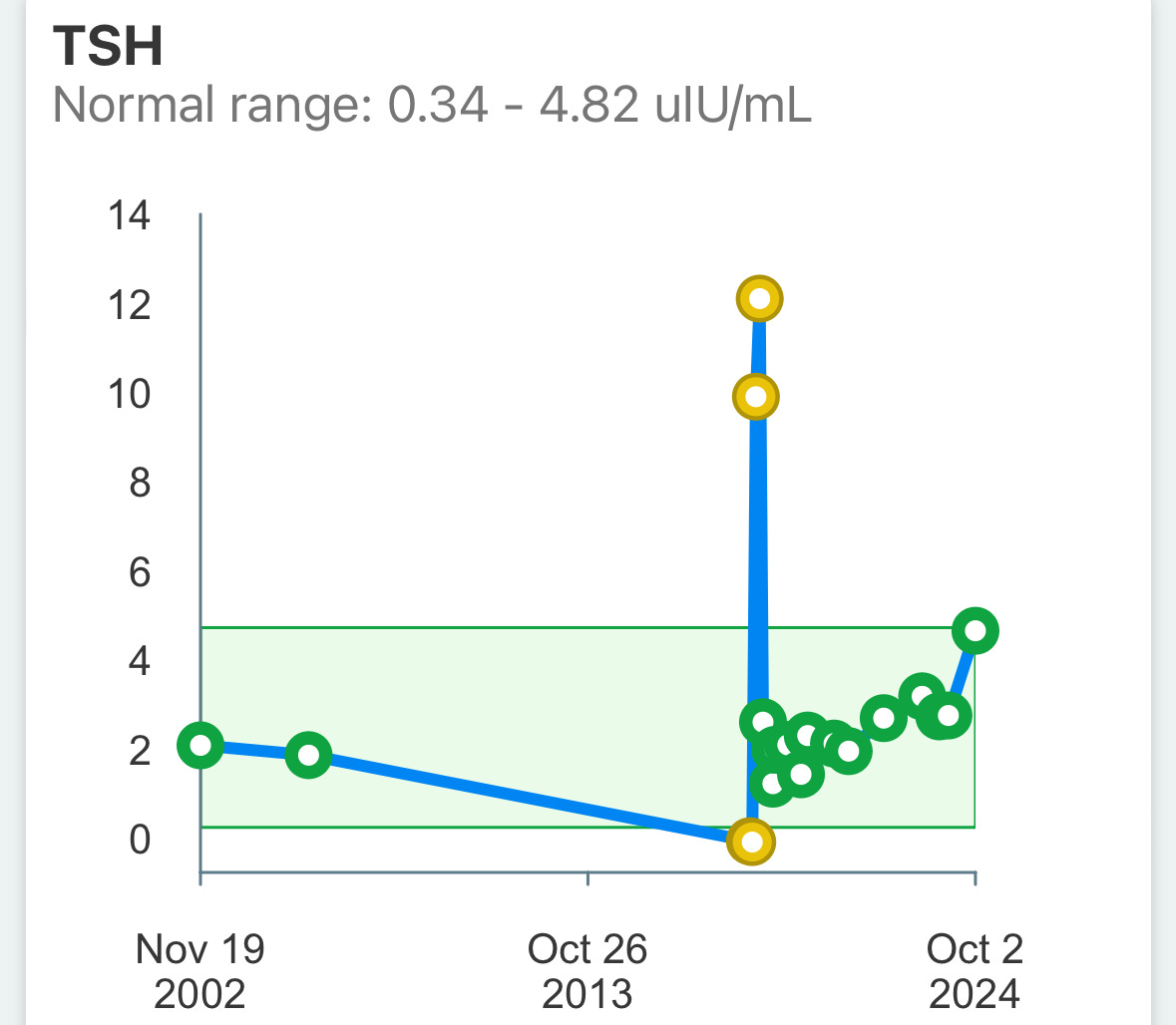

While I have a genetic proclivity for NAFLD and cirrhosis, my lifestyle habits have ensured I have not gotten into that territory. On the other hand, I don’t have a genetic proclivity towards hypothyroidism and yet my TSH results (Figure 12 below) show that I went into the hypothyroid range for a brief period of time because my lifestyle was suboptimal. It wasn’t an issue before that or since then.

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

I want to end by reiterating the point I started with: knowing your genetic tendencies should be viewed as a way to identify which parameters and attributes are worth keeping a closer eye on, and ensuring your lifestyle is tweaked to optimize for those parameters. However, there is neither a reason to become paralyzed by a poor genetic proclivity nor is it justified to take a positive genetic bias for granted. Lifestyle is still key.

For those interested in going through the Nutrigenomics test and counseling for themselves, you can sign up for the test on the preventivehealth.ai website or reach out to nivedita.raut@preventivehealth.ai.

As always, leave your comments on whether you find this helpful, anything you think I can do better, and any topics that I should be covering. Until next time …

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare providers with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or wellness program. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk. The author and publisher of this article make no representations or warranties, express or implied, regarding the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or effectiveness of the information contained herein. The inclusion of specific products, services, or strategies in this article does not imply endorsement or recommendation. The author and publisher disclaim any liability for any adverse effects or consequences resulting from the use or application of the information presented. You are encouraged to consult with a qualified healthcare professional before making any changes to your diet, exercise routine, or lifestyle.

Share this post